Amit M. Kheradia, Environmental Health and Sanitation Manager, Remco (a Vikan company) and Deb Smith, Global Hygiene Specialist at Vikan, discuss best practices relating to cleaning and disinfection of processing equipment parts, even when CIP systems are employed.

In 2015, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that more than 23 million people in Europe fall ill from eating contaminated food every year, resulting in 4,654 deaths. The use of contaminated equipment and utensils is one of the top five contributing causes to foodborne illness outbreaks. Key food safety hazards of public health concern include bacterial pathogens, allergens, chemicals, and extraneous foreign material – and consequently, sanitation methods and equipment capable of minimising the risk of these hazards are required.

Cleaning and disinfection of confectionery production equipment and environmental surfaces (both food-contact or non-food contact) and the maintenance of sanitary conditions is an essential task to ensure product safety and quality, and to meet all relevant regulatory, industry, and global food safety standard requirements.

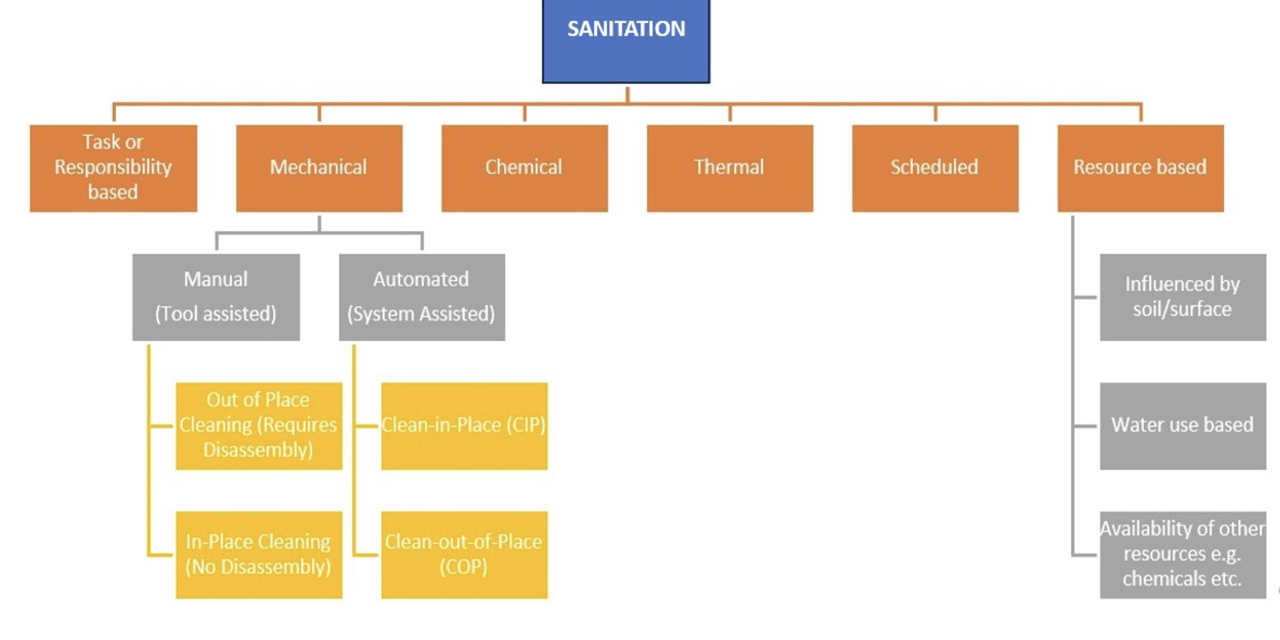

Sanitation involves the removal of visible debris from the surface. This can be achieved in many ways, and a single sanitation method will very often involve overlaps of a variety of sanitation activities.

As Figure 1 shows, sanitation methods can range from being process-specific – such as clean-in-place (CIP) for sanitation of processing pipework and closed vessels – right through to the much simpler, process-agnostic manual cleaning methods which involve the use of a variety of cleaning tools including brushes, scrapers and squeegees.

CIP technology will usually involve the automated sanitation of equipment parts, including the interior of pipes, vessels, or fittings without the need for any disassembly. This is generally done by pumping chemicals at a set concentration, temperature, and pH through the system, for a controlled period, at a flow rate that generates turbulence that provides the mechanical action required as part of the cleaning process in a closed system. Once all the cleaning parameters used by these automated systems have been determined and programmed in, cleaning is as easy as pressing a button. However, the biggest limitation of automated methods such as CIP cleaning relates to the poor hygienic design of some equipment and surfaces. For example, the presence of narrow, inaccessible spaces, or dead-end zones will enable contaminants to get trapped, making it more difficult for the CIP operation to remove. So poorly designed systems do not always allow for a thorough clean using the automated method and this makes manual or tool-assisted mechanical cleaning a necessity.

CIP components such as valves, couplings, probes and sensors, and sampling ports, will also require regular disassembly and manual cleaning to ensure food safety and quality, and the on-going efficiency and effectiveness of the CIP cleaning operation.

Cleaning before disinfecting

If food equipment and surfaces are not properly cleaned, some microorganisms will survive and persist by secreting a slimy, extracellular polymeric substance that can enmesh other organisms, nutrients, moisture, and foreign materials to form a biofilm that can firmly attach to a surface.

According to Moorman and Jaykus (2019), manual cleaning is important for surface biofilm removal because ‘one just can’t sanitise one’s way out of a persistent biofilm problem within a facility. Biofilm eradication, therefore, generally requires equipment teardown, deep-cleaning and sanitation, and a follow-up verification.’

Proper cleaning of equipment and surfaces, therefore, is the first step toward better overall sanitation in confectionery processing plants. So, regular CIP cleaning using turbulence and chemicals, needs to be supplemented, as appropriate, through periodic breakdown and deep cleaning of a system, using manual cleaning to remove surface biofilms. Manual cleaning will always be required, in addition to other cleaning methods, because there will always be hard-to-reach places where biofilms can form and only be effectively removed through manual cleaning.

For any surfaces not sufficiently covered by automated sanitation methods manual cleaning may be the only option. Thus, cleaning and disinfection of equipment and facility surfaces is usually not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ activity because several factors may influence how, when, and why to remove soil from a surface. This may involve creating a manual cleaning plan and selecting the right tools for the right job.

The selection of manual tools is another important consideration as this will influence cleaning efficacy. Choose the right bristle type for brushes and brooms – stiff bristled brushes are good for removing stubborn debris, with or without the use of water, but may damage surfaces, while very soft bristled brushes may be ineffective in removing rigid soils from surfaces but are good for sweeping up fine powders. It is best to use total-colour tools that are easily identifiable, by use or hygienic zone. Segregation of tools in this way also helps reduce cross-contamination issues. Also bear in mind that hygienically designed tools will normally have smooth surfaces, rounded edges, and no crevices where contaminants can accumulate and be difficult to remove after use.

Editorial contact:

Editor: Kiran Grewal kgrewal@kennedys.co.uk